Written by E. Amalia Jansel, Ph.D., Executive Consultant

“It takes something more than intelligence to act intelligently.”

-Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

Early in my career, I had an experience that taught me a thing or two about emotional intelligence. My manager of two years was promoted, leaving behind a close-knit team. The new manager was bringing a strong desire for change. I was not on board, and I was vocal about it.

Six months later, I received my performance review. I exceeded expectations on all criteria, except attitude. My attitude needed improvement. I was shocked. Why did six months go on before I was clued in? I felt it was obvious that my new manager was a terrible leader.

But what makes a great leader?

Author Daniel Goleman (1995) introduced the world to emotional intelligence (EI) as a differentiator, not just in leadership, but also in the workplace and relationships. The concept had been proposed by two researchers (Salovey & Mayer, 1990) intrigued by the evidence of “smart people who make dumb decisions” (Freedman, 2005). It turns out smart decision-making is not solely a function of your cognitive abilities, such as IQ.

At Truist Leadership Institute, we refer to this concept as Conscious Leadership; we recognize that good decisions require conscious leadership (Railey, 2020). Conscious Leadership allows leaders to drive performance and outcomes by:

- Understanding their emotions;

- Understanding how their emotions are different from others’ emotions; and

- Leveraging this information to guide their thinking and actions.

Let’s take a deeper dive into my experience as an example of how leaders can best navigate changes that require teams’ buy-in.

1. Understand your emotions

My manager was genuinely excited about joining our team. We had a track record of accomplishments, and they brought strong expertise to the table – a recipe to continue the winning streak. But we did not eagerly embrace the direction we were taken by this leader who seemed to use every bit of their energy to convince us to go in that direction. Frustration, irritation, and detachment filled the space.

You have probably been there too in your leadership journey. It is not uncommon when embarking on a change to start excited and optimistic about the future, only to find yourself on the verge of pessimism, feeling like you have exhausted every option to get the necessary buy-in from your team.

In these moments of frustration, you might feel with every inch of your body, that you need to push harder, to convince more, to motivate more. However, this approach is unlikely to produce the desired outcomes.

First, you need to pause.

When you are experiencing negative emotions, your limbic system (i.e., the center of the brain where emotions are born) is releasing neurochemicals—specifically cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline—that are affecting the ability of your prefrontal cortex to regulate your emotions and make rational decisions. This process has been described as a “limbic system hijack” - your judgment is clouded not just figuratively, but also literally (Goleman, 1995).

It takes about 90 seconds to flush out the neurochemicals that hijacked your brain (Taylor, 2009). When you feel yourself getting tenser, your heart rate increases, or your breath is shorter, these are signs of limbic system highjack. We recommend pausing and focusing on your breath first.

Secondly, you need to identify your emotions.

Identifying emotions has a calming effect on the limbic system, which in turn allows our prefrontal cortex to get back in command of regulating emotions (Motzkin et al., 2015). Researchers found that if we can clearly identify our unpleasant emotions at a granular level, we can regulate them (Barrett et al., 2001). Clearly identifying emotions is nearly impossible without pausing first.

It was not until recently that the skill of identifying emotions was emphasized in formal education (Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, 2017). I, for instance, had a hard time verbalizing emotions beyond feeling angry or sad. Anger can have a flavor of anxiety, and sometimes frustration. My manager was visibly frustrated, and likely experienced elements of disappointment, fear, and hurt. Cultivating the awareness to identify and label these emotions is an incredibly powerful skill that can help leaders move forward with greater clarity and purpose.

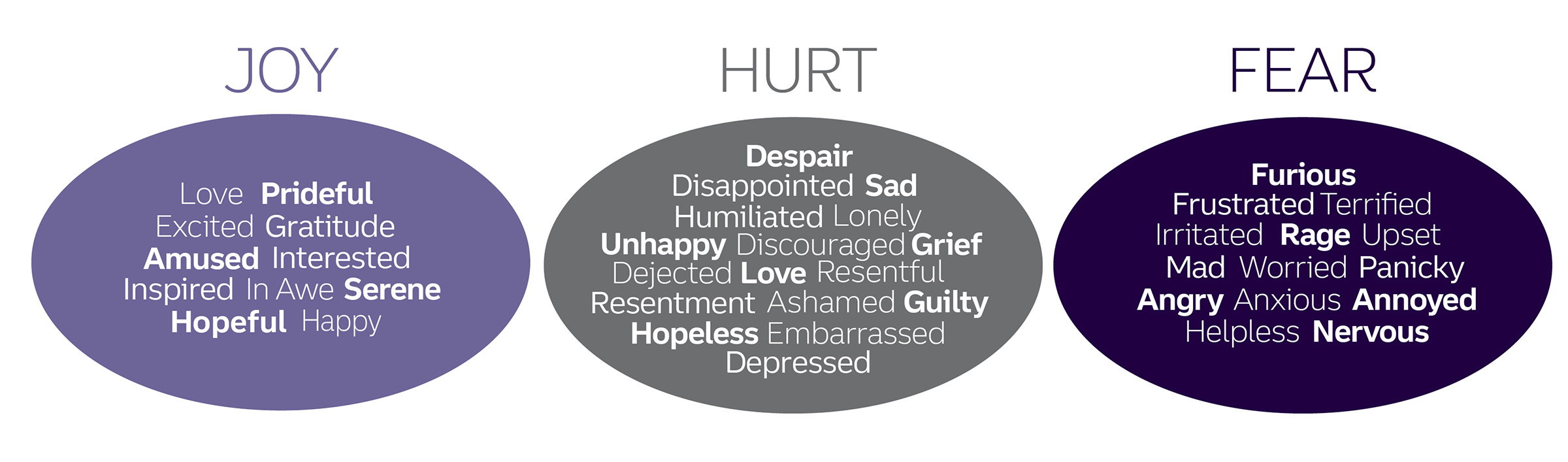

At Truist Leadership Institute, we share a list of emotions classified into three core buckets: fear, hurt, and joy. As you practice pausing, use this list to help you acquire the vocabulary to identify your emotions at a granular level.

When pausing and identifying your emotions, space is created - space to acknowledge and let go of the emotions you are experiencing. Most importantly, space to notice the emotions of others.

When pausing and identifying your emotions, space is created - space to acknowledge and let go of the emotions you are experiencing. Most importantly, space to notice the emotions of others.

Your success as a leader depends on becoming aware of what others might be experiencing. This impacts your ability to tailor communication, address the root causes of roadblocks, and inspire or influence others toward shared outcomes.

2. Understand others’ emotions and differentiate between own and others

I was one of the “others” in this scenario. Why was I resisting the new manager? Why was I not on board with the changes they proposed?

Every negative interaction with the new manager was a reminder of how awesome the previous one was. I was sad, missing the times with my former boss. I was also confused about how I was expected to be. Before, I was rewarded for speaking up, even if that meant constructively critiquing the management of a project. But, with the new manager, it felt like I was consistently being shut down in meetings and like I was being micromanaged.

What makes a great leader is the ability to see others’ emotions and work with them. Plenty of emotions were there from the beginning. Pausing and acknowledging them would have made a difference. I would have seen that the new manager cared about me, about this team, and about what we had built.

Simply understanding emotions does not do much without constructively acting upon the information they provide. I often hear that people are confident they can read the room, but it is harder than it looks, and their actions often don't demonstrate that they are truly paying attention to the feelings and emotions of the people around them.

Great leaders not only understand their emotions and others’ emotions but also intentionally choose their actions based on this understanding.

3. Use your understanding of emotions - your own and those of others - to guide your actions

When things are going well it is easier to pick up on the emotional state of others. When you see your team resisting, your mind is in a space in which you can intentionally choose to offer more support or clarity to move them forward. In highly stressful times, your limbic-system-hijacked brain reads your team’s resistance as a personal attack. Extending empathy feels like a luxury you cannot afford – or, potentially even one that they do not deserve. The urge to react is stronger. A reaction can look like the leader being assertive, combative, or aggressive. Or, it can look like waiting, avoiding, or withdrawing and withholding. My manager's waiting for six months before evaluating me on my behavior could be considered a reaction.

It takes courage to go against the urge to react and instead to pause. When you pause, take inventory of how you can respond in a manner that:

a. is aligned to how you want to be seen as a leader

b. helps promote the culture you intend to build

c. is appropriate for the current situation

If, after you take inventory, you decide that you intentionally want to push harder, you may have also realized that pushing harder is more effective when combined with empathy for your people. For example, consider the differences in outcomes between an unintentional reaction and an intentional response:

Unintentional Reaction: push harder because you are afraid that if you don’t, you will not reach your goals.

Your people might read into your fear. Or they may read your reaction as an attack and get defensive themselves. My entire litany of emotional experiences shared in this article reveals what defensive looks like. Some colleagues were indifferent, and others saw our new leader as untrustworthy and power-hungry. Neither response fueled positive results for our team.

Intentional Response: Push harder because you know that is what is needed, and do so with empathy cultivated by greater emotional awareness.

We had navigated some rapids with our previous leader. We were willing to push harder because the leader took the time to add clarity and check with us about how we were. For example, when the leader was moving too fast and things were unclear or misaligned, we felt safe to share our perspective. And then we continued moving forward as a high-performance team.

Capitalizing on emotional intelligence is one way to help you find the courage to move away from unintentional reactions and toward more intentional, purposeful responses. History is filled with examples of leaders who left their mark by having the courage to demonstrate empathy and integrity in dire times – Empathy - Is It About What to Do or How to Be – while at the same time, pushing unapologetically for key strategic outcomes (Koehn, 2017). These are the leaders who build high-performing organizations and instill the love for leadership in others - like my first leader, who still inspires me today because of the way their emotional intelligence informed how they consistently showed up for our team.